As Featured in Faculty Focus: 15 Years and 15 Ways to Engage Your Students In-Person, Online, and In Zoom

By: Marti Snyder, Ph.D., PMP, SPHR, Professor, Director of Faculty Professional Development, Learning and Educational Center

A variation of this article was published in Faculty Focus on February 11, 2022 – 15 Ways to Engage Your Students In-person, Online, and in Zoom | Faculty Focus

Welcome to the Winter 2022 term! Although we have resumed our classes in their regularly scheduled format (i.e., in-person, hybrid, and online), we continue to practice flexibility in our teaching due to the recent surge of the Omicron variant of COVID-19. Over the 15 years that I have worked at NSU, I have had the opportunity to teach face-to-face, online, and blended courses to undergraduates, master’s, and doctoral students. Here are 15 strategies that I use most often in these various formats to engage my students. Many of these strategies overlap and can be used regardless of delivery mode.

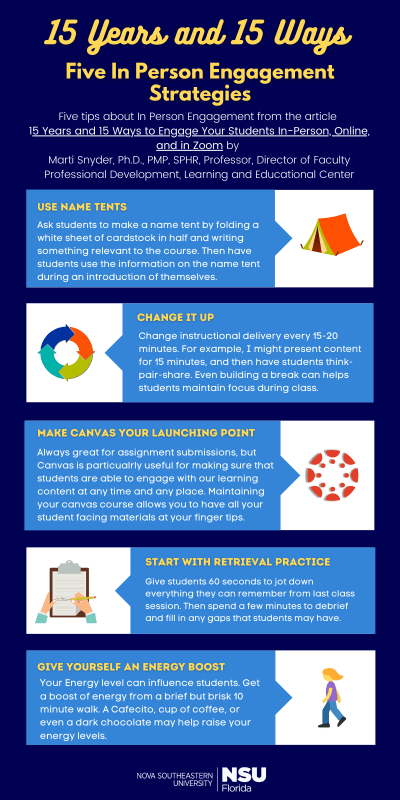

Five In-Person Engagement Strategies

- Use Name Tents: One practice that I have carried over from my days as a corporate trainer is name tents. Name tents are made by taking a white sheet of cardstock and folding it in half. On the first day of class, I give students a blank name tent and colored Sharpie markers and ask them to write their first and last name (the way they would like to be referred to in the class) on the front and the back. That way, I can see their name and so can their classmates. I might also ask them to draw or write something on the name tent that is relevant to the course. For example, when you think of [class name], what is the first thing that comes to your mind. After they create their name tents, we do introductions. During the introductions, they describe what they wrote or drew related to the course topic. Using name tents is helpful in several ways. First, it enables me to call students by their preferred name. Second, at the end of each class, I collect the name tents until the next class. When I pass them out, it helps me to see very quickly who is absent. Finally, it creates a sense of verbal immediacy (Gorham, 1998), which is important when we want to create connections with our students.

- Change it Up: I have taught classes that run from one hour up to three hours. Regardless of the seat time, I change up my delivery every 15-20 minutes. For example, I might present 15 minutes of content followed by some type of active learning technique such as think-pair-share, Socratic discussion, or small group activity. Even a small transition from lecture to a short video clip that illustrates the lecture’s key topics is helpful. I’ve also received feedback from my students that even with the shorter class times, they appreciate a 5- or 10-minute break. These short breaks enable students to return a quick text or phone call, use the restrooms, engage in a short conversation with classmates, or simply decompress.

- Make Canvas Your Launching Point: Over the years, higher education has evolved in its use of technology to support teaching and learning. While Canvas, NSU’s learning management system, was traditionally used for only its online courses, it is expected today that everyone is using Canvas at the very least for assignment submissions. As we learned with the BlendFlex format that we used in 2020, creating a robust course in Canvas can be an effective and efficient way to ensure that our students are able to engage with our learning content at any time and any place. Even for my in-person courses, I create and house everything related to the course in Canvas. That way, when I’m in class, I know where everything is (e.g., PowerPoint presentations, schedules, articles, etc.) and can use our Canvas course to facilitate my in-person class. Preparing the Canvas course in advance also helps me to stay on track with the weekly classes and activities.

- Start with Retrieval Practice: Retrieval practice is a strategy that instructors can use to enhance learning by asking students to recall information from memory (Stachowiak, 2017). At the beginning of each class, I ask students to take out a piece of paper, their tablet, or computer and give them 60 seconds to jot down everything they can remember from our last class together. Sometimes I give them prompts such as: Think about our last class. What did we discuss? What did you learn? Think about the topic we discussed last week. What did you find most interesting? Then, we take a few minutes to debrief what they wrote, which also enables me to fill in any gaps. This strategy not only helps students remember what they learned but it also helps them get focused on the course so together we can move into the new content.

- Give Yourself an Energy Boost: Needless to say, these past two years have been stressful! I have often found myself drained and unmotivated before it is time to teach my class. There are many techniques that I use to give myself a boost of energy (aside from a strong Cafecito, which can keep me up later in the evening that I prefer). During the winter months in South Florida, I’ll go outside for a short but brisk 10-minute walk. Other times, a (no more than) 15-minute power nap is what’s needed. A guilty pleasure of mine is dark chocolate, which has the benefit of caffeine and flavonoids, which have shown to boost cognitive skills and improve mood (Nehlig, 2013). Being energetic and upbeat seems to make my students more engaged and interested.

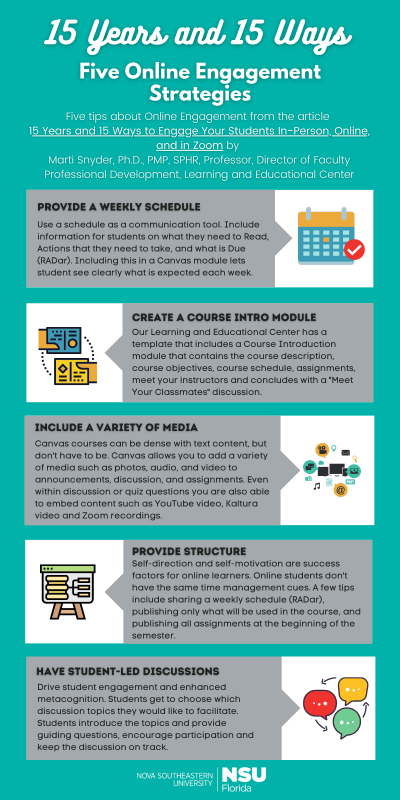

Five Online Engagement Strategies

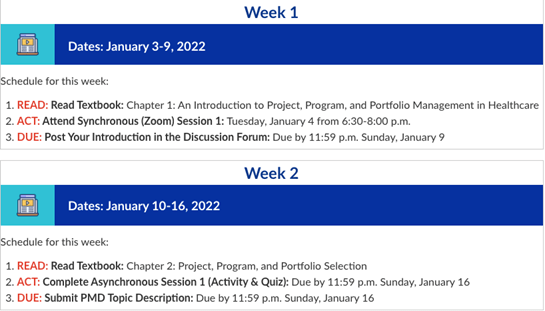

- Provide a Weekly Schedule: My background is in project management so I tend to use project management tools and techniques to run my classes. A useful communication tool is the schedule. I call my weekly schedule the RADar. The RADar includes what students should Read, what Actions they need to take, and what is Due. See Figure 1 for an example.

Figure 1: Screenshot of the Weekly RADar (Read, Act, Do)

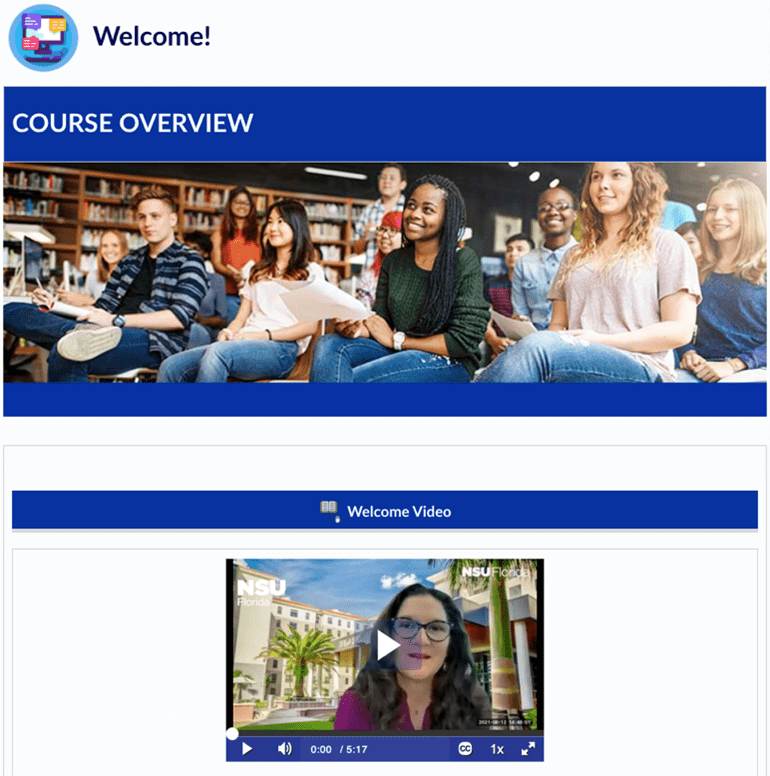

- Create a Course Introduction Module: I started using some of the new templates from the Learning and Educational (LEC) last year. One of my favorite parts of the template is the Course Introduction module. This module includes the course description, course objectives, course schedule, assignments, meet your instructors, and concludes with a “Meet Your Classmates” discussion activity. Figures 2 and 3 show examples of the Course Introduction Module from LEC Template A and Template C.

Figure 2: Screenshot of Course Introduction from LEC Template A

Figure 3: Screenshot of Course Introduction from LEC Template C

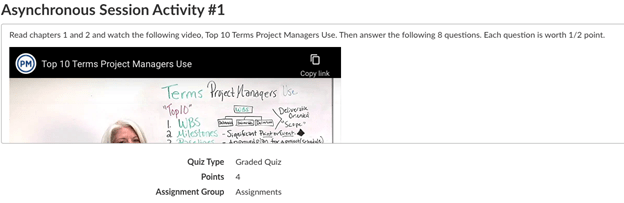

- Include a Variety of Media: I find that my Canvas courses can be dense with text. However, they don’t have to be. Canvas has made it easy to add a variety of media such as photos, audio, and video to my announcements, discussions, and assignments. As Redi pointed out, “…an integration of multiple media elements (audio, video, graphics, text, animation, etc.) into one synergetic and symbiotic whole that results in more benefits for the end user than any one of the media elements can provide individually” (as cited in Mishra & Sharma, 2005, p. vii). Some of the ways I incorporate media into my courses include using images on Canvas pages to support the text; embedding a YouTube video to an online discussion or quiz assignment where students watch the video then post their reactions and thoughts or answer quiz questions; responding to student assignments using audio in addition to text feedback; inserting our course Zoom meetings within the Canvas course using the Embed Kaltura Media feature (which embeds media directly from SharkMedia). Figures 4–6 are examples of how I use a variety of media in Canvas.

Figure 4: Using Images on Canvas Pages to Support the Text

Figure 5: Embedding a YouTube Video into a Canvas Activity in Quizzes

Figure 6: Embedding a Zoom Meeting from SharkMedia using the Embed Kaltura Media Feature

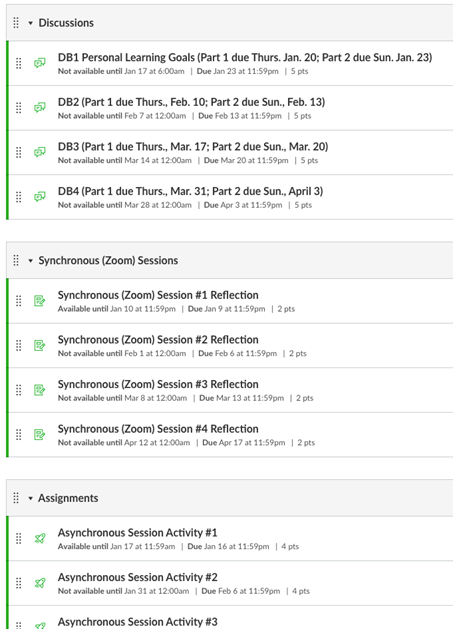

- Provide Structure: Two success factors of online learners are self-direction and self-motivation. In-person classes offer more time management cues such as attending class on a regular basis and completing in-class assignments. In an online course, students must create their own time management and success plan (Darby & Lang, 2019). Providing a well-structured course is one way that I aim to support my students. In addition to the RADar schedule noted earlier, I structure my Canvas course in a simple yet logical way. For example, I only include the Canvas navigation links that we use in the course. I hide the rest. I also organize my modules into categories such as: Introduction, PowerPoints, Readings, and Additional Resources. Something else that I have started to do is publish all of my assignments at the beginning of the semester. That way, students can get a better idea of what to expect. Although students are able to see the assignments, they won’t actually become available to them until a specified date. See Figure 7.

Figure 7: Screenshot of Assignments Module With All Assignments Published

- Have Student-Led Discussions: Student-led discussions can be a strategy for student engagement and enhance metacognition (Snyder & Dringus, 2014). When I implement student-led discussions, I make sure that I provide clear guidelines about their purpose, expectations, and how to facilitate them. At the beginning of the semester, I provide a list of topics and readings and students are instructed to email me indicating their first, second, and third choice of bi-weekly segments to facilitate. I organize the schedule based on their choices and distribute the schedule to the students in Canvas Announcements. Specifically, students are expected to read the assigned reading(s) in advance of their facilitation date, introduce the discussion topic/readings, provide guiding questions for the discussion, encourage participation, keep the discussion focused, encourage multiple viewpoints of the same issue(s), and bring the discussion to and end by summarizing highlights. I also find it helpful if I model the process of student-led discussions before I ask students to do it.

Five Zoom Engagement Strategies

- Implement the Silent/Quiet Meeting: Amazon’s founder and executive chairman, Jeff Bezos, uses silent/quiet meetings for senior executive team meetings. He asks everyone to read a shared memo and make notes for 30 minutes before any discussion begins. This approach is designed when reflection and contemplation are desired (Reigeluth, 1999). It requires attendees to read, reflect, and summarize their thoughts before getting into a more worthwhile conversation. Silent/Quiet meetings can start out with giving everyone a specified time (e.g., 10-30 minutes) to read a common article or passage and take notes before a discussion begins. A tip that I learned from Doug Shaw (http://dougshaw.com/okzoomer/) is something called “The Enter Key is Lava!” In Zoom, you can ask students to type in the chat their response to a specific question or prompt related to the reading but ask them not to press Enter/Return key (it’s lava!) until you instruct them. After the designated time, ask students at the count of three to press the Enter/Return. At that time, everyone’s responses populate the chat box. Give students an additional 5 or 10 minutes to read through everyone’s response and then continue with your discussion about the common read.

- Conduct Socratic Dialogue: Socratic dialogue is a type of discussion in which the instructor guides the learners to discovery through a series of questions (Adler, 1982). Plato first used this method based on his teacher, Socrates, who challenged people’s beliefs and helped them develop their arguments. I have often used Socratic dialogue in conjunction with the silent meeting. Once everyone has a chance to think about and post their initial responses to a topic, I ask guiding questions to dig deeper. I’ve even used breakout rooms for this where I post the guiding questions in the chat, assign students to the breakout rooms, have them discuss, then re-join after 10 or 15 minutes to discuss as a class. It’s important, however, to post clear instructions in the chat about what you want students to do in the breakout rooms before you send them off.

- Use Polling: Zoom polling is an easy way to engage students. I use it as a way to help students practice what they learned in the class. The polls also enable me to check-in with the class to see how things are going. In addition to creating course-related polls, I oftentimes insert questions relating to how they are feeling that day. It gives me a chance to empathize with my students, celebrate their happiness and even discuss strategies to address difficult emotions such as stress and anxiety. In addition to polling in Zoom, NSU has a license to PollEverywhere, which offers more robust polling features. If you would like to request a license, you can send an email to software@nova.edu.

- Enlist the Help of Your Students: It can be difficult to manage both the content, technical, and interactive aspects of a remote session. One of the strategies I use is enlisting the help of my students. At the beginning of the meeting, I ask for volunteers to do various tasks. One student might monitor the chat and bring to my attention the comments and questions. I might assign another student as a co-host and ask that person to help with the technical issues such as muting and unmuting, welcoming students from the waiting room, and creating breakout sessions. I also ask for volunteers to lead the breakout discussions. Enlisting the help of students not only keeps them engaged in the course but it also helps me run a more efficient class.

- Plan for Zoom Downtime: We’ve heard about Zoom fatigue and Zoom burnout. Even a 30-minute Zoom session can be exhausting. I’ve implemented intentional downtime to help me and my students in the Zoomosphere. Downtime can involve asking everyone to turn off their cameras for a set period of time. Students do various types of activities while the camera is off such as simply listening to a lecture to working on a particular activity to doing something creative and fun like a virtual scavenger hunt. The scavenger hunt can relate to the course or it can be used to create community as an ice breaker.

Conclusion

Regardless of what course delivery format you teach in, I hope you find these strategies useful in connecting with and engaging your students. I am interested in learning about the strategies that you use as we can learn from each other. Please email your strategies to smithmt@nova.edu with the subject, “Teaching Strategies.” I also welcome you to join the LEC’s MAKO Commons, and online virtual community of practice for NSU educators. Our mission is to connect faculty across NSU so that we can share ideas, information, and resources related to research and practice in teaching and learning. Here’s a link to more information and how to join: https://www.nova.edu/lec/MAKO_Commons.html

Check out the infographics based on the article, click on the image to enlarge.

References

Adler, M. (1982). The paideia proposal: An educational manifesto. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Darby, F. & Lang, J. (2019). Small teaching online: Applying learning science in online classes. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Gorham, J. (1988). The relationship between verbal teacher immediacy behaviors and student learning. Communication Education, 37, 40-53.

Mishra, S. & Sharma, R.C. (2005). Interactive Multimedia in Education and Training. Hershey, PA: Idea Group Publishing.

Nehlig, A. (2013). The neuroprotective effects of cocoa flavanol and its influence on cognitive performance. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 75(3), 716-727.

Reigeluth (1999). What is instructional-design theory and how is it changing? In Reigeluth, C. (Ed). Instructional-design theories and models: A new paradigm of instructional theory (vol. II, p. 22).

Shaw, D. (n.d.). Okay Zoomer: Going beyond the basics: Repurposing Zoom tools for increased engagement. http://dougshaw.com/okzoomer/

Snyder, M. M. & Dringus, L.P. (2014). An exploration of metacognition in asynchronous student-led discussions: A qualitative inquiry. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 18(2), 29-48.

Stachowiak, B. (Host). (2017, December 21). The science of retrieval practice with Pooja Agarwal (No. 184) [Audio podcast episode]. In Teaching in higher ed. https://teachinginhighered.com/podcast/science-retrieval-practice/