Annoto: New Social Interaction Feature Available in Canvas

NSU has just rolled out a new tool that you can use in your Canvas courses called Annoto. Annoto has many great features that will engage your students while they are viewing videos. This tool transforms the video-watching experience from a passive one into an active one and can be used with any video you choose. It enables learners to contribute, share, and learn together, experience videos as an interactive group, and keep a personal journal of notes. It allows instructors to guide the video-watching experience with questions, formative assessments, and focused discussions, as well as the ability to answer questions related to the video. Every interaction in Annoto is time-tagged to a specific part of the video so it is very easy to align interactions with the appropriate part of the video. There is also a notification system so students can be alerted, for example, when the instructor answers their questions or responds to their comments.

NSU has just rolled out a new tool that you can use in your Canvas courses called Annoto. Annoto has many great features that will engage your students while they are viewing videos. This tool transforms the video-watching experience from a passive one into an active one and can be used with any video you choose. It enables learners to contribute, share, and learn together, experience videos as an interactive group, and keep a personal journal of notes. It allows instructors to guide the video-watching experience with questions, formative assessments, and focused discussions, as well as the ability to answer questions related to the video. Every interaction in Annoto is time-tagged to a specific part of the video so it is very easy to align interactions with the appropriate part of the video. There is also a notification system so students can be alerted, for example, when the instructor answers their questions or responds to their comments.

One of the problems with videos as a method of delivering instruction is that they often involve passive viewing which doesn’t engage the student as much as desired. Classic video players only allow viewers to move through videos in a linear manner with basic controls such as play/stop and backward/forward options (Sauli et al., 2017). This type of video viewing does not support deep-learning processes such as reflection, elaboration, or annotation (Sauli et al., 2017). Just as important as the quality of the video itself, is to present the video in a format that demands student engagement beyond passive viewing (Fyfield et al., 2019). A tool like Annoto gives instructors the ability to utilize certain elements of what some scholars call “hypervideo,” such as the ability to use annotations within the video interface, the ability to interact and exchange ideas with shared comments, and the ability to receive feedback through communication tools or assessments (Sauli et al., 2017).

Interaction and social communication are valuable tools for learning (Preece et al., 2002, as cited in Ebner, 2014). Interactive tools allow learners to explore ideas in different ways that are useful for a variety of content types, especially for difficult or abstract ideas (Sharp et al., 2019). Students who are socially engaged during learning through interactions such as following other students or collaborating in discussions are more likely to complete courses and graduate (Sunar et al., 2017). One of the biggest benefits of a tool such as Annoto is the ability to make and share annotations – as the name suggests. Interactions and reflections through hypervideo annotations are different from commenting in discussion groups because the annotations take place while watching the video, which makes for a more active learning experience (Blau & Shamir-Inbal, 2021). Annotation of video gives students the opportunity to engage with audiovisual content in a participatory way rather than in a passive-receptive mode (Colasante & Douglas, 2016). Zahn et al. (2010) found that advanced video tools that involve annotations allow for deeper and more focused discussions and enhanced learning compared to classic playback options. It must be noted, however, that hypervideo tools work best when they are accompanied by planned student activity and feedback (Laurillard, 2002). While Annoto can give some immediate feedback through peer comments and formative assessments, the biggest results in terms of improvement in learning will come from structured pedagogical practices, instructor guidance, and instructor feedback (Blau & Shamir-Inbal, 2021). Instructors should plan the interactions or storyboard the lesson to achieve the best results.

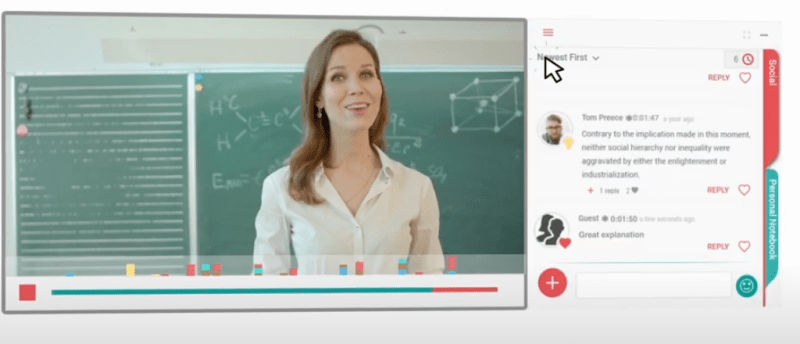

The way Annoto works is that it places an overlay next to the video which displays the interactions. During the video playback, an instructor can ask a guiding question, for example, at a specific point in a video. Students will then be directed to respond as prompted. The questions could be used to reflect on the information from the video, direct a discussion among students, or to assess whether the information was learned. Instructors can create formative assessments utilizing a variety of question types at any point in the video. These assessments can include automatic feedback and instructors can choose from multiple settings and preference options such as time limits, number of attempts, and whether to allow students to re-watch a portion of the video. Students can also post any questions or comments they have related to specific points in the video. This can be a great feature since multiple students may have a similar question and when you answer one student, they can all benefit from the answer. There is an indicator that shows whether a post was made by the instructor or a student. Students and instructors can post audio or video comments and even links to outside sources. This feature can be used as an activity where students are directed to find or create examples of a concept and post the link in the Annoto stream, or as a way for students to introduce themselves to the class. Through all these features, instructors and students can easily interact in a collaborative viewing and learning experience.

The way Annoto works is that it places an overlay next to the video which displays the interactions. During the video playback, an instructor can ask a guiding question, for example, at a specific point in a video. Students will then be directed to respond as prompted. The questions could be used to reflect on the information from the video, direct a discussion among students, or to assess whether the information was learned. Instructors can create formative assessments utilizing a variety of question types at any point in the video. These assessments can include automatic feedback and instructors can choose from multiple settings and preference options such as time limits, number of attempts, and whether to allow students to re-watch a portion of the video. Students can also post any questions or comments they have related to specific points in the video. This can be a great feature since multiple students may have a similar question and when you answer one student, they can all benefit from the answer. There is an indicator that shows whether a post was made by the instructor or a student. Students and instructors can post audio or video comments and even links to outside sources. This feature can be used as an activity where students are directed to find or create examples of a concept and post the link in the Annoto stream, or as a way for students to introduce themselves to the class. Through all these features, instructors and students can easily interact in a collaborative viewing and learning experience.

All interactions in Annoto are time-tagged with a link so the instructor or student can go to the exact point in the video where the interaction took place. There is also an interactive timeline that displays which parts of the video have comments along with a bar that shows the magnitude of comments at each point. While the student is engaging, the video pauses for them so they don’t fall behind. Students and instructors also get a private notebook where they can take notes that are time-tagged to the appropriate place in the video. Students can use this to mark insights, record thoughts, or make a summary of the video. Instructors may want to mark points in the video to focus on with the class or that they find notable. These notes are saved and can be exported, which is a great benefit to both students and instructors. This feature can also be used as an activity where students are directed to make insights or reflections on the video and then export the file to turn in as an assessment.

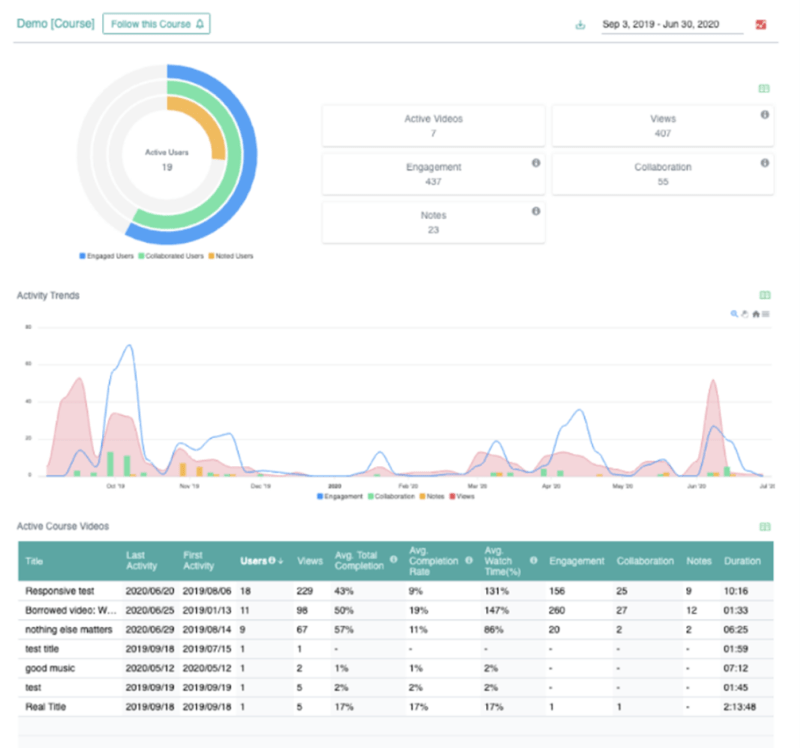

Along with a host of options for the interactions and general settings, Annoto’s dashboard gives instructors insight and reporting on student activity. The reporting is comprehensive including the ability to see who watched each video, for how long, and how many times they watched it. You can also see the types and number of interactions students had with the video and each other. Instructors can also read and respond to comments directly from the dashboard. There are analytics for the entire course, for each video, and for each student.

Along with a host of options for the interactions and general settings, Annoto’s dashboard gives instructors insight and reporting on student activity. The reporting is comprehensive including the ability to see who watched each video, for how long, and how many times they watched it. You can also see the types and number of interactions students had with the video and each other. Instructors can also read and respond to comments directly from the dashboard. There are analytics for the entire course, for each video, and for each student.

If you are interested in learning more about Annoto, please join us for the upcoming training sessions.

References

Blau, I., & Shamir-Inbal, T. (2021). Writing private and shared annotations and lurking in Annoto hyper-video in academia: Insights from learning analytics, content analysis, and interviews with lecturers and students. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(2), 763–786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-09984-5

Colasante, M., & Douglas, K. (2016). Video annotation “Prepare-Participate-Connect” models: Promoting student learning. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 32(4). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.2123

Fyfield, M., Henderson, M., Heinrich, E., & Redmond, P. (2019). Videos in higher education: Making the most of a good thing. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(5), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.5930

Laurillard, D. (2002). Rethinking University Teaching : a converstional framework for the effective use of learning technologies. Routledgefalmer.

M Almusharraf, N., Costley, J., & Fanguy, M. (2020). The effect of postgraduate students’ interaction with video lectures on collaborative note-taking. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 19, 639–654. https://doi.org/10.28945/4581

Sauli, F., Cattaneo, A., & van der Meij, H. (2017). Hypervideo for educational purposes: A literature review on a multifaceted technological tool. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 27(1), 115–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939x.2017.1407357

Sharp, H., Rogers, Y., & Preece, J. (2019). Interaction design: Beyond human-computer interaction (5th ed.). Wiley.

Sunar, A. S., White, S., Abdullah, N. A., & Davis, H. C. (2017). How learners’ interactions sustain engagement: A MOOC case study. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 10(4), 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1109/tlt.2016.2633268

Zahn, C., Pea, R., Hesse, F. W., & Rosen, J. (2010). Comparing simple and advanced video tools as supports for complex collaborative design processes. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 19(3), 403–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508401003708399